The EFC Holds True to Its Roots

By Debra Fieguth

Article written for Faith Today’s Sep/Oct 2004 issue. See below for an online-only timeline of the EFC’s first 50 years or jump to a 16-page 50th anniversary booklet published in Faith Today in Jan/Feb 2014.

The Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, formed by a group of pastors in 1964 in order to promote fellowship, cooperation and a united voice to media and government, has grown and matured without abandoning that original vision.

As the new pastor of Danforth Gospel Temple in Toronto in the early 1960s, Harry Faught noticed his colleagues tended to stick to their own denominations. “There were so many good men, but it seemed to me they weren’t having anything to do with each other,” recalls Faught, a Pentecostal. “They all worked independently of each other. I thought it had to be a good thing if we had more fellowship together.”

Faught had enjoyed meeting with Christians from other churches when he was a student at Dallas Seminary in Texas. So he tried, informally at first, to promote more cooperation among Toronto pastors. Their resistance surprised him. Once he asked Oswald J. Smith, founding pastor of The Peoples Church, to speak to his congregation. “He said, ‘I don’t speak in other churches in Toronto.’ And that was such a perplexity to me.” Smith changed his mind, however, and Faught kept building bridges.

He began meeting with a handful of other pastors, including Arthur Lee of Calvary Church and Harold Telfer of Temple Baptist. Faught had attended some meetings of the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) in the U.S. and was keen to have a parallel group in Canada. Clyde Taylor, who headed the NAE, encouraged the formation of a similar group and even attended some Canadian meetings.

In 1964 at least a couple of hundred ministers met at Knox Presbyterian, pastored by William Fitch. “That was the last sort of ad hoc meeting,” says Faught.

Out of that meeting, The Evangelical Fellowship of Canada was born, with Faught as its first president and Smith as its honorary president.

The main goal from that inauspicious beginning 40 years ago was to promote understanding and fellowship among churches. “We were viewed cautiously among the old line churches,” recalls Faught. “My own denomination thought that to be involved in something outside of ourselves had to have some compromise. They got over this later on.”

It wasn’t exactly national at the time, but there was a sprinkling of ministers from the Kitchener and Niagara areas who came on board from the beginning. Within a few years, the fellowship did become national in scope. In 1967 Faught crossed Canada with American theologian Carl F.H. Henry, holding meetings from Vancouver to Halifax and inviting individuals to join the EFC. It was shortly after the “God is dead” philosophy had permeated Western culture, and Henry spoke about the rise of theism that followed.

Over the next two decades the fellowship started commissions to study various issues, published a magazine called Thrust, sponsored preaching seminars and encouraged cooperation among evangelical denominations and individuals from mainline churches. Presidents and executive members came from Presbyterian, Alliance, Brethren, Baptist, Associated Gospel, Pentecostal and other churches. [Editor's note: Other early leaders, after Bill Fitch, included Mariano DiGangi, Bob Thompson and Don Macleod, some of whom also helped birth World Relief Canada.]

The budget was bare bones and, apart from some paid secretarial help, there was “no remuneration for anybody, time-wise or travel-wise,” recalls Faught. There were some tough times: John Irwin, who was treasurer of the EFC in the early 1970s, remembers a moment in the parking lot after his father’s funeral when he, board member Jim Clemenger and others signed notes on the hood of a car to go to the bank and borrow money to keep the organization afloat.

Tackling Social Issues

Brian Stiller had been watching the development of the EFC since he was a student at the University of Toronto and attended the organization’s second annual meeting in 1965. A Pentecostal from Saskatoon, Stiller looked to Harry Faught as his mentor and shared his interest in evangelicalism. To him, Faught “represented the kind of evangelicalism I aspired to and wanted to be a part of.” Stiller saw the core values—the centrality of the cross, the authority of Scriptures, the fellowship of believers and the importance of sharing the good news—as things evangelicals could share without compromising their denominational distinctives.

Stiller joined the staff of Youth for Christ and later became its national director, participating in the EFC at the same time. He was named chair of the social action commission in 1978 and was later appointed to the fellowship’s executive.

Stiller joined the staff of Youth for Christ and later became its national director, participating in the EFC at the same time. He was named chair of the social action commission in 1978 and was later appointed to the fellowship’s executive.

By 1981 the EFC had concluded it was time to hire a full-time director, even though there was no money in the budget to do so. Stiller was on the search committee. A conversation in the fall of 1982 with Mel Sylvester, then president of the Christian and Missionary Alliance and an EFC executive member, was a turning point for Stiller.

“He looked across the table and said, ‘Don’t you think it’s time you left YFC and took on this assignment?’” Unbeknownst to Sylvester, Stiller had just told his YFC board chair that he was leaving his job—without knowing what he would do next.

Stiller became the first executive director of the EFC in the spring of 1983 and quickly transformed the organization, building its individual membership to 17,000 and expanding its budget. By the time he left in 1997 the budget had grown from about $60,000 a year to more than $3 million.

The fellowship also began to take its place in Canadian society. For Stiller, a key goal was to help evangelicals understand the role they could have in engaging the public and government. “We had so long vacated that role,” he says. To that end he developed a seminar called Understanding Our Times and took it across the country.

Under Stiller, the EFC became a more visible presence. “What became obvious to me was that evangelicals were looking for a voice,” he recalls, “a voice to government and a voice to media.”

Stiller began building relationships on Parliament Hill, most notably with Jake Epp, a cabinet minister in Brian Mulroney’s Conservative government, and with parliamentary secretary Len Gustafson (now a senator), who got Stiller into the Prime Minister’s Office. “That showed the political community that we were a bona fide group with something valuable to offer,” says Stiller.

One of the key issues the EFC got involved in also landed one of its biggest blows. In 1988 the Supreme Court of Canada struck down the country’s abortion law in a move that became known as the Morgentaler decision. A carefully crafted bill was meant to introduce a new law that would be acceptable to most Canadians. But it involved a compromise, and was voted down by pro-choice MPs as well as strident evangelicals and Roman Catholics. The result? Canada is “now the only country in the Western world that has no legal protection for the unborn.” Stiller calls the loss “one of the worst moments in my whole 14 years” at the EFC.

During his tenure, Stiller launched an issues-related television program—first called The Stiller Report and later Cross Currents—on the new Vision TV station, and remodeled the EFC’s flagship publication from Thrust into Faith Alive and then Faith Today. He also became a frequent guest on television and radio programs. By 1996 Stiller fulfilled the dream of opening an office in Ottawa.

Facilitating Ministry Partnerships

When Stiller accepted an invitation in 1997 to become president of Ontario Bible College and Seminary (now Tyndale University College and Seminary), Gary Walsh became president. Walsh, who was bishop of the Canadian Free Methodist Church, began to focus specifically on ministry partnerships.

Walsh “picked up a thread that had been woven into the pattern all along but had not been addressed in an intentional way,” comments Aileen Van Ginkel, director of EFC’s Centre for Ministry Empowerment, who worked closely with Walsh. [UPDATE: The CME has been succeeded by the current Centre for Ministry Partnership and Innovation.]

There was a new emphasis on nurturing partnerships. Denominations, organizations, educational institutions and congregations began to share their resources for a common purpose. Together they created ministry “roundtables”—on evangelism, global mission, higher education, Christian media and more recently on poverty and homelessness. The EFC was the catalyst in the formation of these roundtables, and it continues to support them with financial, administrative and communications help, explains Van Ginkel, who has worked with the EFC for 15 years. These partnerships continue to gain momentum and are enabling increased ministry effectiveness.

Simultaneously, as Walsh encouraged the EFC leadership to embrace this role more intentionally, international evangelical networks began increasingly to call on the EFC to help them with this work.

Simultaneously, as Walsh encouraged the EFC leadership to embrace this role more intentionally, international evangelical networks began increasingly to call on the EFC to help them with this work.

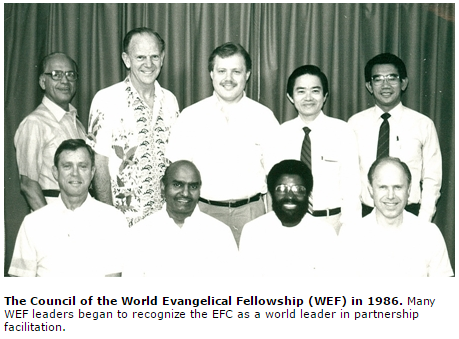

At first, Walsh says, he was surprised to hear leaders of the World Evangelical Alliance talk about the EFC as a “world leader” in partnership facilitation, but the label proved accurate. Some of the initiatives set in motion at that time have led the EFC to the point today that it regularly shares its expertise internationally.

Under Walsh’s leadership there was also more emphasis placed on gathering the community, both literally—through events such as the annual Presidents Day, when leaders of affiliated denominations, institutions and some congregations get together—and virtually, through a new web site, www.christianity.ca. [UPDATE: That site closed in 2022.]

The new emphases on partnerships and gathering are consistent with the original vision, says Van Ginkel. Creating a forum for evangelicals to meet and share together is “right there at the heart of Harry Faught’s vision.”

Mobilizing For Ministry and Public Witness

In the late 1970s, Bruce J. Clemenger, then a Toronto student, joined thousands of Canadian evangelicals across the country who participated in church-sponsored events based on Francis Schaeffer’s popular book and film series called How Should We Then Live? This idea of integrating personal faith with life motivated him throughout his university years when he studied economics and history, and later political philosophy.

He had grown up witnessing a commitment to cooperative evangelicalism. His dad, Jim Clemenger, had served on numerous boards, including the EFC’s. “I remember that through my father’s work the idea of communication and cooperation across denominational lines was very familiar,” Clemenger recalls. “That was part of the assumption and ethos he lived.”

Clemenger grew up with links both to missionary organizations and political figures. One of the EFC’s early presidents, federal politician Robert Thompson, was an old family friend. Living in a non-sectarian environment that mixed politics, ministry and business gave Clemenger a rich appreciation for the broader evangelical Church. “The impression, for me, was that denominations had distinctives that were important, but they weren’t walls or barriers.” It was just assumed that ventures would cross denominational lines.

Having served with the international relief agency Samaritan’s Purse and after returning to graduate school to study political philosophy, Clemenger joined the EFC’s social action commission in 1989. He came on staff in 1992 as research coordinator, then moved into working with national affairs, public policy and legal interventions. In 1996 he moved to Ottawa to open an office to provide a more consistent presence there, and in 2003 was named president of the EFC. During these years he became the primary spokesperson for the EFC in matters of law and public policy. [UPDATE: Clemenger's job titles switched Jan. 1, 2023 to EFC senior ambassador and president emeritus.]

Having served with the international relief agency Samaritan’s Purse and after returning to graduate school to study political philosophy, Clemenger joined the EFC’s social action commission in 1989. He came on staff in 1992 as research coordinator, then moved into working with national affairs, public policy and legal interventions. In 1996 he moved to Ottawa to open an office to provide a more consistent presence there, and in 2003 was named president of the EFC. During these years he became the primary spokesperson for the EFC in matters of law and public policy. [UPDATE: Clemenger's job titles switched Jan. 1, 2023 to EFC senior ambassador and president emeritus.]

The establishment of the Centre for Faith and Public Life in Ottawa, which today is led by Janet Epp Buckingham, is the fulfilment of a long-time dream for many [UPDATE: The CFPL is now led by Julia Beazley]. Even in the early days, says Charles Tipp, a Fellowship Baptist pastor from Niagara Falls who became the first secretary, EFC founders thought about having representation in Ottawa, much as the NAE lobbied for evangelicals in Washington. Harry Faught also remembers hoping for a stronger role in Ottawa back in the 1960s.

“Since they opened the Ottawa office there’s more of a presence in government circles,” he notes, “which was something we were hoping for and working towards.”

How does the EFC look in 2004 in view of its early goals of fellowship, cooperation and a united voice? “I think in many ways we continue to fill out and expand and mature those original impulses,” says Clemenger, who sees the organization as “helping to mobilize evangelicals by promoting collaboration for ministry and public witness.”

The EFC continues to grow as a gathering place for evangelicals and a national forum for collaboration. In its 40th year it has increased to 40 affiliated denominations. The number of affiliated ministry organizations and churches is also growing. New ministry partnerships continue to be formed, and the EFC is increasingly being sought out by government agencies and media for comment on matters of faith as well as politics. New initiatives include Celebration 2005, designed to help mobilize churches to share the gospel in creative ways, and plans to open an office in Quebec. And as the second largest national evangelical association in the world, the EFC is involved in several initiatives to assist the growth of sister national alliances, to address the persecution of Christians, and to build international ministry partnerships addressing issues such as HIV/AIDS in Africa.

Edify, Equip, Speak from Consensus

Applying biblical principles to contemporary issues is a thread that has been woven into the EFC fabric over the years. Just how to apply those principles remains a tricky balancing act. For Mariano DiGangi, a Presbyterian minister who was president of the EFC in the early 1970s, it means helping evangelicals to understand the issues and think about them. “I think that wherever we have some key issues, we should have scholarly papers that can be made available to help shape our own thinking,” he says. Although the issues might change, “the principles to be applied remain the same.”

Clemenger goes further. “The need for a strong voice promoting biblical principles in the public square is vital, as it is to provide resources to help evangelicals think about how biblical principles apply to some very complex issues,” he says. When the EFC makes submissions in a political or judicial case, “we seek to advance the application of biblical principles in public life, and on many issues there is general agreement on the general policy implications of these principles. Yet there is also considerable diversity among evangelicals on politics; we don’t vote as a bloc and we cannot claim unanimity or a like mind where it does not exist. ”

Church historian John G. Stackhouse Jr. concurs. Attempting to speak for such a large and varied group of Christians is difficult, says Stackhouse, a professor at Regent College in Vancouver [UPDATE: He is now an independent scholar]. “The vector is to edify the church, inform us about what’s going on and then equip us to do better in the political sphere.”

Clemenger understands the complexity of representing such a diverse group on matters of law and public policy. “Yet there are some issues on which even evangelical politicians from different political parties will vote together. Our commitment is to foster dialogue on the implications of biblical principles for contemporary society and—where there is a consensus—to speak boldly.” Where there is no discernible consensus, such as on the death penalty, “we don’t advance a position.”

There will continue to be lively debate about the role evangelicals and the EFC can and should play in Canadian society and especially in politics. One thing is sure, however: the fellowship will continue to challenge Christians to reflect deeply on the issues in our culture and respond to them.

“How do we deal with the broader implications of living our faith in the public realm?” It’s a question that Bruce J. Clemenger and other thoughtful Canadian Christians continue to ponder, long after the Francis Schaeffer film series was shown across the country, and 40 years after a fledging organization called The Evangelical Fellowship of Canada took flight.

Debra Fieguth is a Kingston freelancer who has been writing stories for Faith Today since 1986 [UPDATE: Debra passed away in 2016 and is greatly missed.]

The EFC’s First 50 Years

By Bill Fledderus

What follows is a year-by-year summary of the EFC’s history based on the most easily accessible materials. Corrections on the information below are welcome at editor@faithtoday.ca.

1964: The EFC was founded in Toronto by a group of pastors to promote fellowship and co-operation across denominational lines. Similar groups had formed in the United Kingdom in 1846 and in the United States in 1942. Harry Faught, a Pentecostal, was the first president. Oswald Smith of Peoples Church was honorary president. William (Bill) Fitch, pastor of Knox Presbyterian, hosted the founding gathering and later served as president. That same year, Canada adopted its current maple leaf flag.

1967: Faught crossed Canada inviting individuals to join the EFC. Faught and others began to dream of having evangelical lobbyists in Ottawa. Canada celebrated its centennial anniversary and saw 50 million people visit Expo ’67 in Montreal. The EFC published a magazine called Thrust. Regular issues were produced until 1983, when it was succeeded by Faith Alive.

1970s: The EFC established a social action commission to study various issues. It ended in 2000, as the staff at the EFC’s Ottawa office took on some of this work in the late 1990s. The EFC also sponsored preaching seminars and encouraged cooperation among evangelical denominations and individuals from mainline churches. EFC leaders in the early 1970s included Don MacLeod, Mariano DiGangi, Bob Thompson, John Irwin and Charles Yates. The TV show 100 Huntley Street began broadcasting in 1977.

1978: Brian Stiller was named chair of the EFC social action commission and was later appointed to the fellowship’s executive.

1980s: Mel Sylvester was EFC leader in the early 1980s. Canada’s new Constitution and Charter of Rights and Freedoms were proclaimed in 1982.

1983: Stiller was hired full-time as the EFC’s first executive director. He remodeled Thrust into Faith Alive (a temporary name until the preferred name, Faith Today, became available).

1985: The EFC helped facilitate the merger of two relief agencies to become World Relief Canada. Its precursors were Share Canada (founded in 1972 by four Christian and Missionary Alliance pastors) and the World Relief Commission of Canada (a ministry of The Peoples Church, Toronto).

1986: Stiller began building relationships with individual politicians and staff on Parliament Hill. Audrey Dorsch was appointed editor of Faith Today, a position she would hold until 1995. Among her duties were organizing regional conferences, called God Uses Ink, to develop more Christian writers.

1987: The EFC established a task force on evangelism, which held a major congress in 1990. The task force shifted to become Vision 2000, then Vision Canada, and finally National Evangelism Partnerships before ending in 2007.

1988: Canada’s abortion law was struck down as unconstitutional because its complexity prevented equal application across the nation. The Associated Canadian Theological Schools (ACTS) was founded to bring together the seminaries of Fellowship Baptist, Conference Baptist, and Evangelical Free denominations at Trinity Western University in British Columbia.

1989: Bruce J. Clemenger joined the EFC’s social action commission. Three years later, in 1992, he was hired as a research coordinator, then moved into working with national affairs, public policy and legal interventions. The EFC intervened in the Supreme Court over the constitutional status of the unborn (Borowski v. Canada). The EFC held a national conference on human life to develop a declaration on human life. Denise O’Leary wrote a book, The Issue Is Life. The EFC established a task force on education to study various issues. It was later renamed the education commission and lasted until 2000, as the staff at the EFC’s Ottawa office took on some of this work in the late 1990s.

1990: A new abortion law, Bill C-43, passed from Parliament to the Senate. It would have retained abortion as a criminal offence but permitted it on broad grounds. It was opposed by some pro-lifers who deemed it ineffective and by many abortion advocates who found it too restrictive.

1991: Bill C-43 passed two votes in the Senate, but faced a tie vote on its third and final reading. The Speaker of the Senate cast a tiebreaker vote against the bill. Since this failure, Canada has not passed any abortion legislation.

1992: The EFC’s task force on Canada’s future, founded in 1991, published a book of essays, Shaping a Christian Vision for Canada: Discussion Papers on Canada’s Future. The EFC also published several books by Brian Stiller including Generation Under Siege (1990), Critical Options for Evangelicals (1991), Don’t Let Canada Die by Neglect (1994) and Was Canada Ever Christian? (1996).

1993: A startling Angus Reid poll found 15 per cent of Canadians to be "evangelical." Controversially, only eight per cent identified with evangelical churches, while another two per cent identified with mainline Protestant denominations and five per cent with the Roman Catholic Church. The EFC intervened in the Supreme Court about the legal status of assisted suicide (Rodriguez v. British Columbia). The EFC established a women in ministry task force, later known as the Forum for Women in Ministry Leadership. It ended in 2003. The EFC convened a consultation on poverty which led to the establishment of a roundtable on poverty and homelessness, later to launch as an independent organization called Street Level. The EFC's task force on the family published a report, Clergy Families in Canada.

1994: Brian Stiller launched an issues-related TV show (The Stiller Report, later called Cross Currents) on Vision TV, a new faith-oriented channel. He became a frequent guest on other TV and radio programs. He dreamed of opening an office in Ottawa.

1995: The EFC established an Aboriginal Task Force, later renamed the Aboriginal Ministries Council. It ended in 2012. The EFC and its evangelism initiative Vision 2000 published the book In Search of Hidden Heroes: Evidence That God is at Work. Faith Today published cover stories on the Toronto Blessing (authored by Gail Reid, later to become editor) and Promise Keepers.

1996: Clemenger moved to Ottawa to open an EFC office there, the Centre for Faith and Public Life. The EFC intervened in Adler v. Ontario, a case which considered the province’s refusal to fund independent religious schools.

1997: Stiller accepted an invitation to become president of Ontario Bible College and Seminary (now Tyndale University College and Seminary). Gary Walsh became EFC president, restructuring the organization and strengthening its focus on facilitating ministry partnerships. The World Evangelical Fellowship held its 10th General Assembly in Abbotsford, B.C., with EFC staff heavily involved. The EFC established a task force for global mission (now called the global mission roundtable) as well as a religious liberty commission.

1998: The EFC facilitated a post-secondary education roundtable, later to become an independent organization named Christian Higher Education Canada.

1999: The EFC appointed Janet Buckingham as general legal counsel, a position she held until 2003. That year she took on a new title, director of law and public policy, which she held until 2006. Then she left the EFC to head the Laurentian Leadership Centre, an Ottawa satellite program of Trinity Western University.

2000: The EFC established what would become known as the Child in Church and Culture Partnership. It ended in 2011. The EFC and Vision Canada produced the book Moved With Compassion: Stories of Canadian Christians Living Out God’s Love. Gail Reid was appointed managing editor of Faith Today and director of communications of the EFC, a position she would hold until retiring in 2013.

2001: The EFC established a Youth & Young Adult Ministry Roundtable. The EFC intervened in the Supreme Court about child pornography laws (R. v. Sharpe), following up on years of previous advocacy to get these child porn laws added to the Criminal Code. Faith Today handed off its writing awards and writers conferences to The Word Guild, a new Canadian association of writers and editors. The EFC intervened in Trinity Western University v. College of Teachers, a case which considered whether public benefits could be withheld from a private Christian university because it had a lifestyle policy that prohibited students from engaging in homosexual practices.

2002: The EFC intervened in the Supreme Court about a genetically designed mouse, with the court agreeing that living, breathing beings can't be subject to patent (Harvard College v. Canada). The EFC intervened in Chamberlain v. Surrey School District No. 36, a case which considered the right of parents to express a religiously informed position on education policy.

2003: Clemenger became EFC president. He clearly articulated the EFC’s approach to matters of law and public policy in a Faith Today article: the EFC’s “commitment is to foster dialogue on the implications of biblical principles for contemporary society and – where there is a consensus – to speak boldly. Where there is no discernible consensus, such as on the death penalty, we don’t advance a position.” The EFC launched a new website, Christianity.ca, to provide “a virtual gathering place for the Canadian Christian community.” It republished thousands of articles from Canadian Christian print periodicals or written by Christians in secular publications, making them more widely accessible. Around this time the EFC restructured various ministry roundtables. David Macfarlane, who had been an active participant in Vision 2000, came on staff at the EFC for several years as director of national initiatives. The EFC established Presidents Day, an annual invitation-only gathering of leaders of EFC affiliate denominations, ministry organization and post-secondary schools.

2004: The EFC intervened in a series of legal cases about extending the definition of marriage to include same-sex couples, an issue kicked off by provincial court decisions in 2002 and not resolved until 2007. Faith Today published a cover story on The Passion, a controversial new movie by Mel Gibson that contributed to an upsurge in mainstream, religiously oriented films. Faith Today articles celebrating the EFC’s 40th year noted it had increased to 40 affiliated denominations. “New ministry partnerships continue to be formed, and the EFC is increasingly being sought out by government agencies and media for comment on matters of faith as well as politics. New initiatives include Celebration 2005, designed to help mobilize churches to share the gospel in creative ways, and plans to open an office in Quebec. And as the second largest national evangelical association in the world, the EFC is involved in several initiatives to assist the growth of sister national alliances, to address the persecution of Christians, and to build international ministry partnerships addressing issues such as HIV/AIDS in Africa.” The EFC intervened in two cases in Quebec about religious freedom, including the duty of municipalities to facilitate the building of houses of worship through zoning and permits.

2005: The EFC’s Geoff Tunnicliffe was appointed as CEO / Secretary General of the World Evangelical Alliance, an appointment renewed for a second five-year term in 2010.

2006: The EFC facilitated Street Level, a conference on poverty that released the Ottawa Manifesto, nine statements directed at citizens and government to help alleviate poverty. One of Faith Today’s most widely read issues, “Faith and Politics,” was published in the lead-up to a federal election, including articles by top Canadian leaders including Stephen Harper, Jack Layton and Paul Martin. A series of Faith Today columns by theologian Victor Shepherd reflecting on the EFC's statement of faith (a statement almost identical to that of the World Evangelical Alliance) was published in book form, entitled Our Evangelical Faith.

2007: Christian Higher Education Canada, a partnership the EFC helped to found, became independent. The EFC Centre for Research on Canadian Evangelicalism began publishing an online journal, Church and Faith Trends. The new centre also published a book, Community Research Guide for Church Leaders.

2008:The EFC produced a DVD video package of recordings of its Christian Leaders Connection seminars, entitled Shifts: Changing Gears to Advance Issues Facing the Church in Canada Today.

2009: The EFC intervened in Alberta v. Hutterian Brethren of Wilson Colony, a case which considered the collective right to religious freedom of a community of believers. Looking ahead to the 2010 Olympic Winter Games in Vancouver, the EFC and other groups successfully pushed for improvements to Canada’s laws on human trafficking. The EFC produced a DVD video package of recordings of its Christian Leaders Connection seminars, entitled Being Evangelical in a Complex World.

2010: The EFC intervened in the Supreme Court on federal regulation of genetic technologies, another piece of legislation the EFC had previously advocated (Reference re: Assisted Human Reproduction Act).

2011: The EFC intervened in S. L. v. Commission scolaire des Chenes, in which Christian parents requested their children be excluded from a Quebec school curriculum teaching religion as equivalent to mythology. The EFC Facebook page surpassed 13,000 “likes.” Brian Stiller returned to EFC orbit in his new role as global ambassador for the World Evangelical Alliance. The EFC promoted adoption within the Christian community in various ways, including a new website AdoptionSunday.com. Several partnerships facilitated by the EFC launched into independence, including the Canadian Marriage and Family Network, Equipping Evangelists, Purpose at Work, and the Canadian Network of Ministries to Muslims.

2012: The EFC intervened in Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission v. William Whatcott, a case which considered human rights codes and religious beliefs. An important study of young adults, entitled Hemorrhaging Faith, was released. The EFC co-operated with Defend Dignity in efforts to educate Canadians about prostitution law reform. The EFC began to publish its Canada Watch newsletter six times per year; previously it had been quarterly.

2013: The EFC intervened on the issue of prostitution laws, first in the Bedford case at the Supreme Court and later by releasing an influential report, Out of Business: Prostitution in Canada - Putting an End to Demand. The EFC intervened in the Rasouli case at the Supreme Court, and welcomed the court's decision about how to handle ending life support. The EFC magazine Faith Today celebrated its 30th anniversary.

2014: The EFC intervened in three Supreme Court cases: the Loyola case on religious freedom in education, the Carter case on euthanasia and the Saguenay case on religious freedom (prayer at government meetings). Decisions are not expected until 2015. The Canadian government passed new prostitution laws, an area of public policy that the EFC had been intervening in for more than a decade. Quebec passed a controversial law legalizing euthanasia. The EFC partnered with the Canadian Bible Forum in an important study on Bible engagement in Canada. The EFC supported an affiliate, Trinity Western University, through legal controversy as it developed Canada's first private law school.