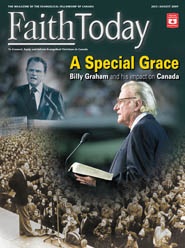

Two of Billy Graham’s greatest contributions are his integrity and the international networks he helped to found

By Bruce J. Clemenger

Most Evangelicals I have spoken to have memorable Billy Graham experiences. Mine began when I volunteered as a teen counsellor for a showing of the movie Time to Run and later in various roles at the 1978 Toronto mission. Later still, working with Samaritan’s Purse Canada, I talked one-on-one with Billy Graham as we ate hamburgers. In 1986 at the Amsterdam Training Conference for Itinerant Evangelists, I worked with Ruth Graham to distribute donated clothing to evangelists who had little. Ruth worked hard to locate a wedding dress for a poor evangelist – in his culture the groom had to provide the dress. Such personal moments gave me a glimpse into the life and ministry of someone who has come to personify evangelicalism for many.

Most Evangelicals I have spoken to have memorable Billy Graham experiences. Mine began when I volunteered as a teen counsellor for a showing of the movie Time to Run and later in various roles at the 1978 Toronto mission. Later still, working with Samaritan’s Purse Canada, I talked one-on-one with Billy Graham as we ate hamburgers. In 1986 at the Amsterdam Training Conference for Itinerant Evangelists, I worked with Ruth Graham to distribute donated clothing to evangelists who had little. Ruth worked hard to locate a wedding dress for a poor evangelist – in his culture the groom had to provide the dress. Such personal moments gave me a glimpse into the life and ministry of someone who has come to personify evangelicalism for many.

Many accolades about Billy Graham focus on his message and character.

His fame was built on his effective presentation of the fact that we are all sinners and Christ died to forgive us of our sins and to put us in a right relationship with God. He also harnessed the power of television. But he did both in a way that transcended American culture – a rare achievement. His simple style and message enabled him to be sought out by government leaders and welcomed in cities around the world. He is the best known of the best of evangelists and is a global representative of evangelicalism. He has borne this responsibility well.

Graham’s fame has also meant that he, his late wife and the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association have consistently operated under close scrutiny. The character evident in the Grahams and their co-workers remains a model for others. Charles Templeton, a former close colleague who rejected the Christian faith, became a critic of evangelists and wrote a disparaging novel about an evangelist. Yet he never uttered a negative comment about Graham, even when asked.

The character evident in the Grahams and their co-workers remains a model for others

Graham’s clear and forthright presentation of the gospel and his character opened many doors critical to his effectiveness. He boldly and unapologetically engaged his critics. This earned respect from Evangelicals. He had legitimacy, hence authority, among Evangelicals and he used this wisely and judiciously.

No one else but Billy Graham and his organization could have pulled off Amsterdam ’86. Imagine bringing together 10,000 evangelists from 100 countries with simultaneous translation offered in 12 languages (the only common word being “hallelujah”).

Another critical international initiative was The Lausanne Movement and the resulting covenants that have defined evangelicalism theologically for more than a generation. Graham saw the need for evangelical leaders from around the world to gather and come to agreement on themes such as the authority of Scripture, the lostness of all people and salvation in Christ alone, witness in word (proclamation) and deed (social responsibility) and the necessity of evangelism.

The statements on evangelism and social responsibility flowing out of the Lausanne Covenant (1974) and the Manila Manifesto (1989) are critical in framing a more integrated and socially dynamic faith than what characterized evangelicalism at the turn of the past century.

And they are being reclaimed again in this century. What many are now calling the missional church, a church that is outward focused and reaching out into communities in word and deed, is a manifestation of the theological groundwork laid by Graham and others such as John Stott.

Now it is no longer personalities but organizations that have this global ability to convene key gatherings. Two of these organizations, the World Evangelical Alliance and The Lausanne Movement, are joining together to hold a major congress on world evangelization in South Africa in 2010. They do so on the theological framework that was forged by Graham’s call. He used his influence to gather leaders who have set the agenda that defines contemporary evangelicalism.

Author:

Bruce J. Clemenger